About

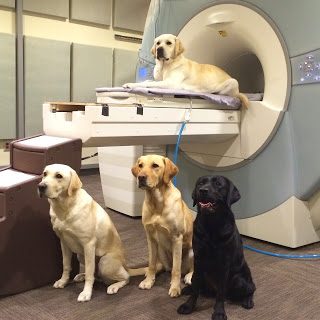

Dogs have had a prolonged evolution with humans. Because of this, many of their cognitive skills are thought to represent a selection of traits that make dogs particularly sensitive to human cues. But how does the dog mind actually work? To answer this question, researchers at Emory University and Comprehensive Pet Therapy have been trainings dogs to lay still in an MRI – completely voluntarily and without sedation.

The “Dog Project” began in 2012. Initially, two dogs were trained using positive reinforcement. The dogs learned to hold an extended down-stay in a custom-made chin rest inside a simulated MRI. They also learned to wear ear protection to guard against the noise an MRI makes as well as becoming acclimated to the sounds. Within a few months, we had performed the first scans in the world. We demonstrated that the reward system of the dog’s brain could distinguish between hand signals that meant the presence or absence of a food reward.

We currently use fMRI to study canine cognitive function in awake, unrestrained dogs. The goals of these projects are to non-invasively map the perceptual and decision systems of the dog's brain and to predict likelihood of success in service dogs.

fMRI and Decision-Making

Greg's research is aimed at understanding the neurobiological basis for individual preferences and how neurobiology places constraints on the decisions that people and animals make. To achieve this goal, we use functional MRI to measure the activity in key parts of the brain involved in decision making. For example, we have used this activity to predict the commercial success of popular songs — the first prospective demonstration in neuromarketing. These results have found application in understanding common stock investing errors, and more recently, in the stock market's reaction to earnings announcements. We have also studied decision-making over "sacred values" in the brain and its implications for terrorism.

Background

For decades, neuroscientists, psychologists, and economists have studied human decision making from different perspectives. Although each has approached the problem with different theories and techniques, the basic question is common to many fields: why do humans make the choices that they do? And, given that humans sometimes exercise poor judgment in their decisions, what can we do about it?

Economists have developed simple theories of decision-making, for example, that are used to understand the movement of asset prices in markets. The basic theory says that people make decisions in such a way as to achieve outcomes that maximize their benefit. Although more mathematically precise, it has much in common with psychological theories that say that people tend to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. Although these theories describe basic tendencies of all animals, they often fail to account for decisions in common circumstances. For example, when individuals must make decisions in which an immediate benefit must be weighed against long-term consequences, they usually choose immediate gratification. Diet and preventive health care often fall prey to this temporal myopia. So do retirement savings.

The idea behind neuroeconomics is simple. The brain is responsible for carrying out all of the decisions that humans make, but because it is a biophysical system that evolved to perform specific functions, understanding these physical constraints may help explain why people often fail to make good decisions.

The emphasis in neuroeconomics has been on individual decision making. There is, however, potential for taking these techniques to a much larger, globally important level: collective action.

Why Collective Decision Making?

Very few decisions are truly individual. Even choices that we make that seem individualistic, like what to wear, where to live and work, what to eat, either directly or indirectly involve the consideration of impact to other people. People organize their lifestyles, in large part, in response to people around them and what society says to do. Understanding how social factors affect the valuation of lifestyle decisions may have a major impact on public policy, for example. Although this type of social effect is important, it is still about the individual.

All of the global crises that we currently face are problems of collective decision making. We live in a world with limited (and diminishing) resources. How the human race decides to manage its resources is the most important decision we have ever faced. Everyone realizes that what happens over the next few decades will determine the face of human life on the planet.

The problems are daunting: climate change, hunger, disease, energy, war. What makes these problems even more frustrating is that we possess the technology to come up with solutions to all of them.

The real problems are human nature and the difficulty in getting 6 billion people to agree on anything.

What Can Be Done?

Collective decision making is political.But politics are biological. There is ample evidence showing that human traits that we have assumed were socially acquired (like fairness and altruism) evolved because they provide survival advantages. Their darker counterparts, like xenophobia, also have biological underpinnings. Understanding how the brain makes decisions in collective settings, how it trades off individual self-interest against collective good, and what the brain's physical limitations are may point to solutions that the usual ways of thinking do not. A recent study on fairness, for example, found that the right prefrontal cortex is responsible for judging fairness, and by manipulating activity in this part of the brain, individuals could be changed from spiteful to forgiving. Similarly, we need to understand how religious and political ideologies, which are abstract social values, become transformed in the brain such that they can subvert basic self-survival value judgments. That is one thing that is unique about the human brain: its ability to convert abstract ideas into actions with value (positive or negative).

Only by elucidating how our brains are wired to behave in group settings can we figure out solutions to problems of global impact.